Constitutive modeling of transversely isotropic rocks

Anisotropic modified Cam-Clay model:

I have developed a constitutive model to capture the anisotropic mechanical response of transversely isotropic rocks by extending the modified Cam-Clay model with an alternative stress state transformed with a rank-four projection tensor that contains the information of the spatial orientation of the bedding structures[1]. Using the proposed model, I conducted stress-point simulations of plane strain compression test on overconsolidated Tournemire shale, and the result is demonstrated in the figure below:

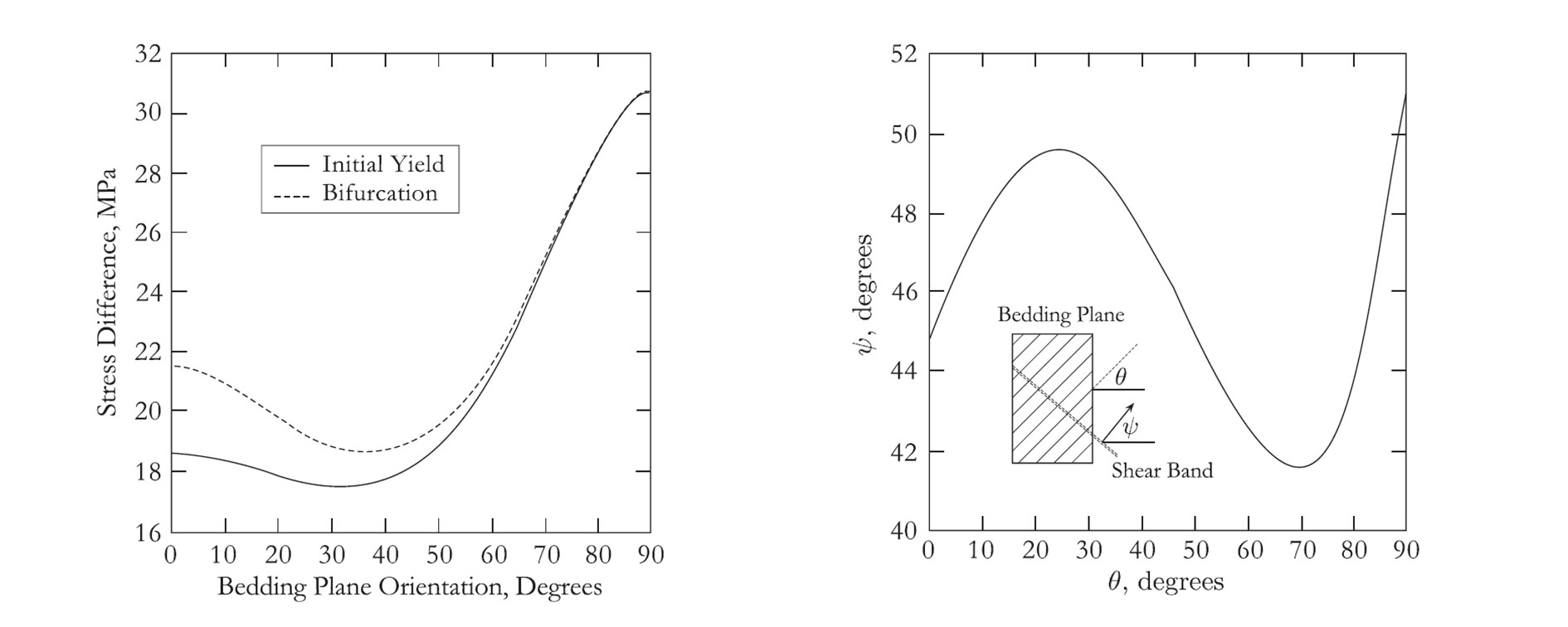

Stress-point simulation results of plane strain compression test on Tournemire shale.

Variations of (left) rock strength (right) failure plane orientation with bedding plane orientation.

It shows that the proposed model can generate a U-shaped variation curve of rock strength with bedding plane orientation, which is often observed in laboratory experiments. The result also indicates that strain localization at the material-point level tends to occur along the weaker bed-normal direction.

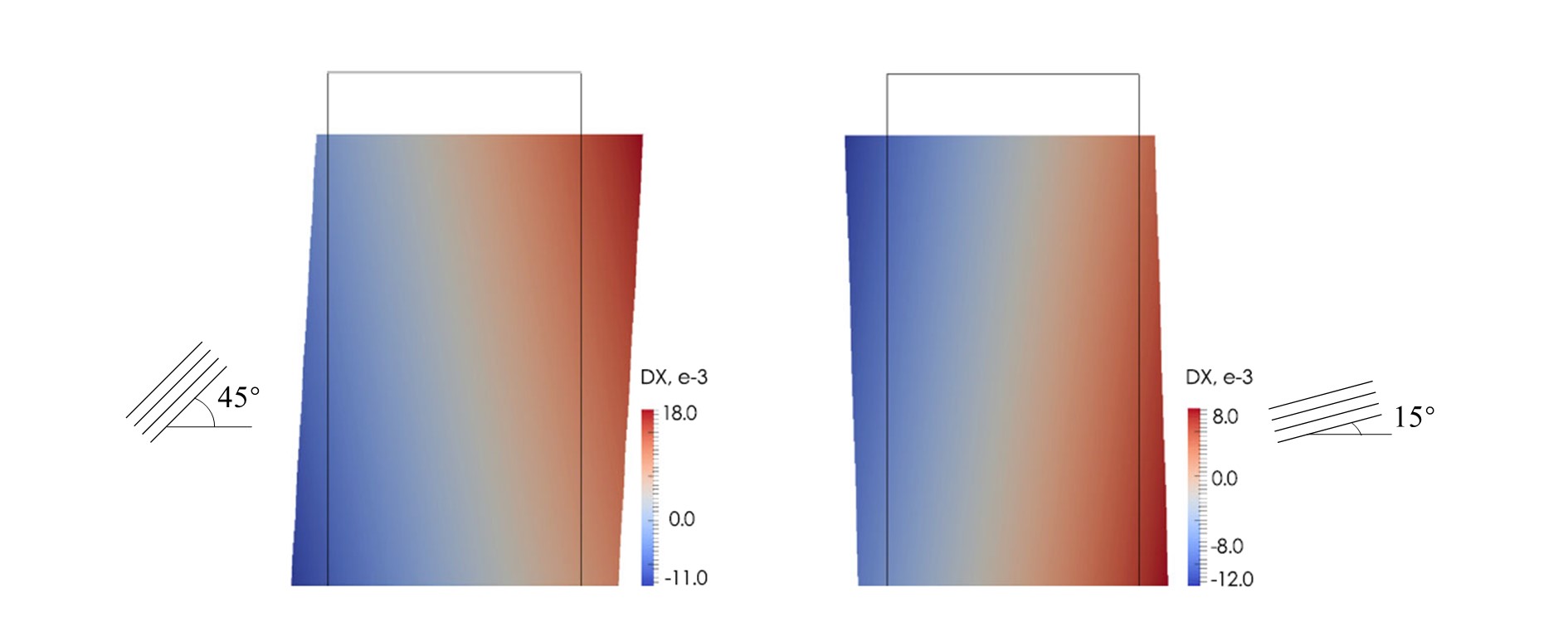

On the same material, we conducted finite element simulations found that while the specimen deform in a homogeneous manner, the sample will swing due to material anisotropy, and the swing direction could be opposite given different bedding plane orientations, as demonstrated in the figure below:

Swing effect of specimen in plane strain compression tests.

bedding plane orientation equals (left) 45° (right) 15°.

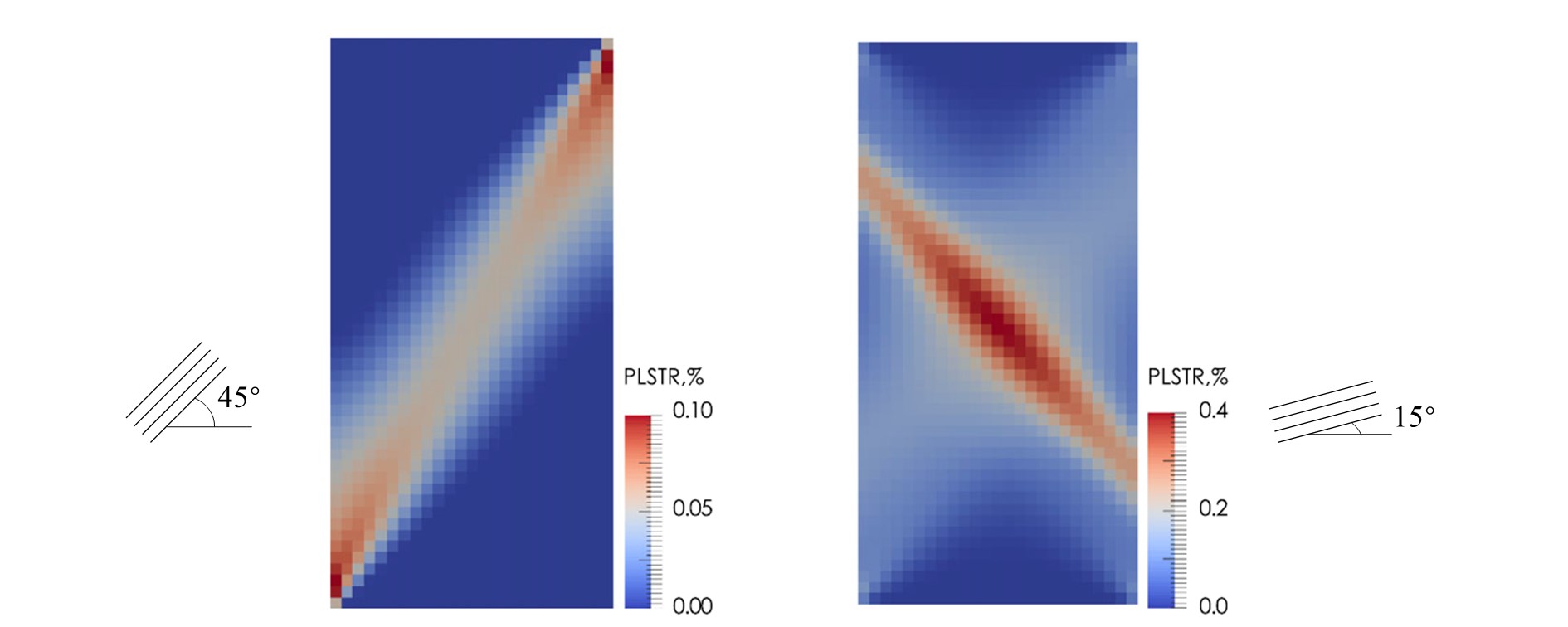

Accordingly, if both bottom and top ends were clamped and the swing of the specimen were restricted, we would get localized shear bands in the specimen triggered by the end constriants, propagating along either bed-normal direction or bed-parallel direction:

Shear bands triggered by end contraints. bedding plane orientation equals (left) 45° (right) 15°.

As demonstrated above, both strain localization at material level and end contraints can lead to shear failure, and the two factors working together may lead to complex zigzagged failure patterns commonly observed in laboratory experiments on shale.

Cam-Clay IX model:

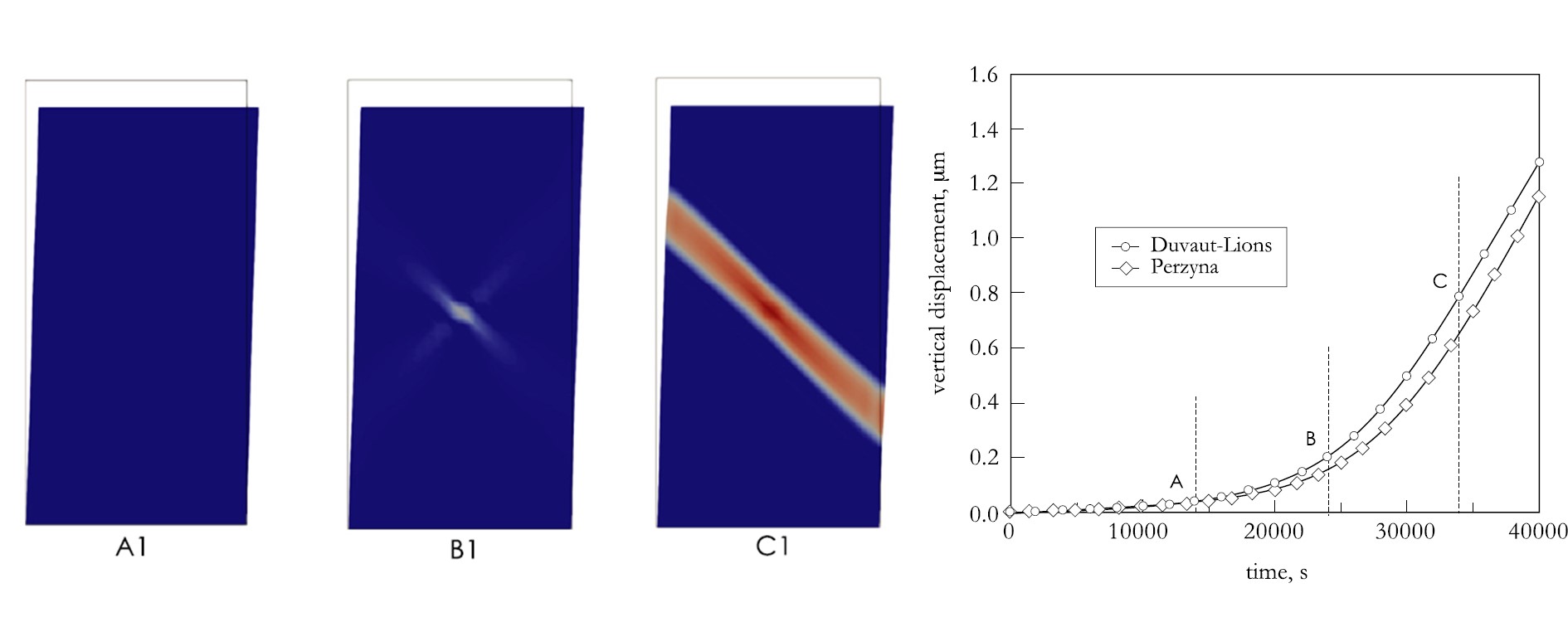

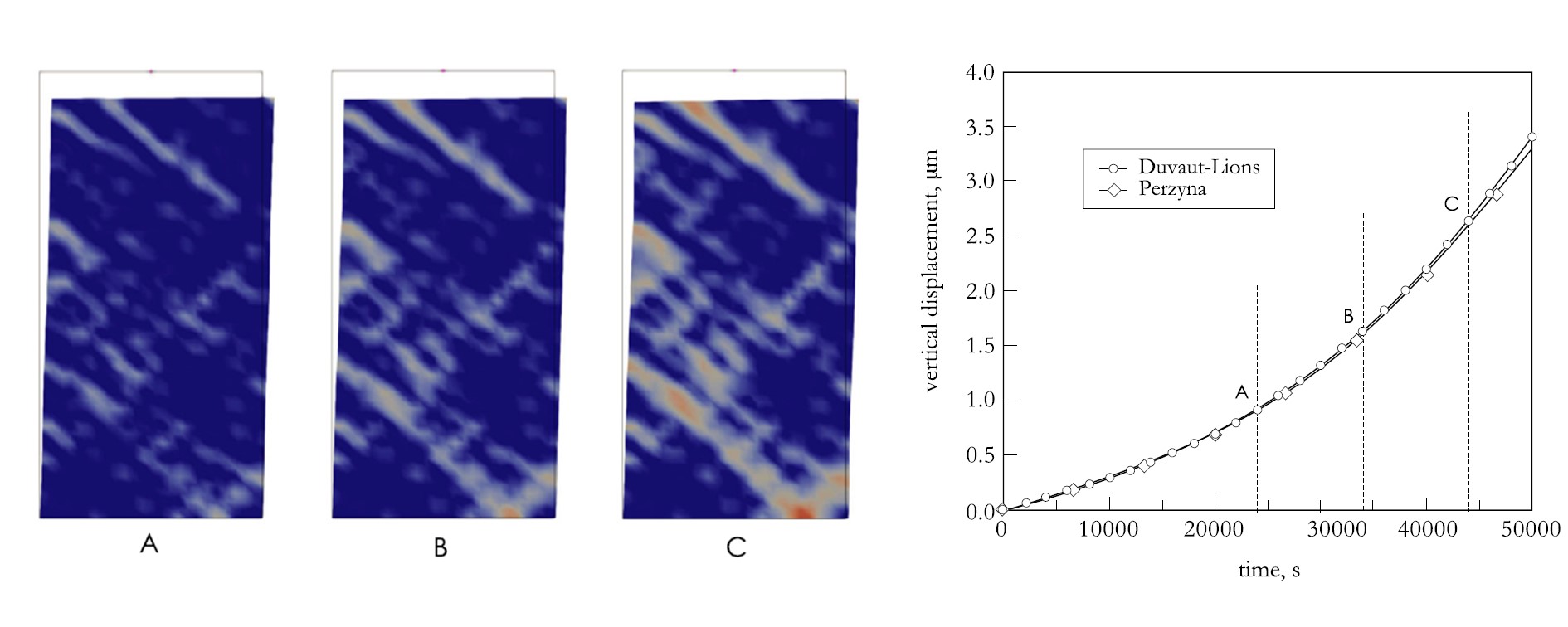

As a contributing author, I contributed to the development of the Cam-Clay IX model that considers anisotropy, material heterogeneity, and viscoplasticity of shale[2]. This model can properly quantify the mechanical response of shale with different material compositions. Besides, it can capture time-dependent processes such as creep and relaxation in shale. Moreover, for the first time reported in the literature, we showed that a shear band can form in a shale specimen even with a constant load when the viscosity in its mechanical response is considered, a phenomenon we called “creep-induced strain localization”. The following figures demonstrate the evolution of creep induced shear bands in a specimen with a weak spot, and in a specimen consists of heterogeneous materials:

Creep induced strain localization in specimen with a weak spot.

Creep induced strain localization in specimen with heterogeneous material distribution.

Double-yield-surface plasticity model:

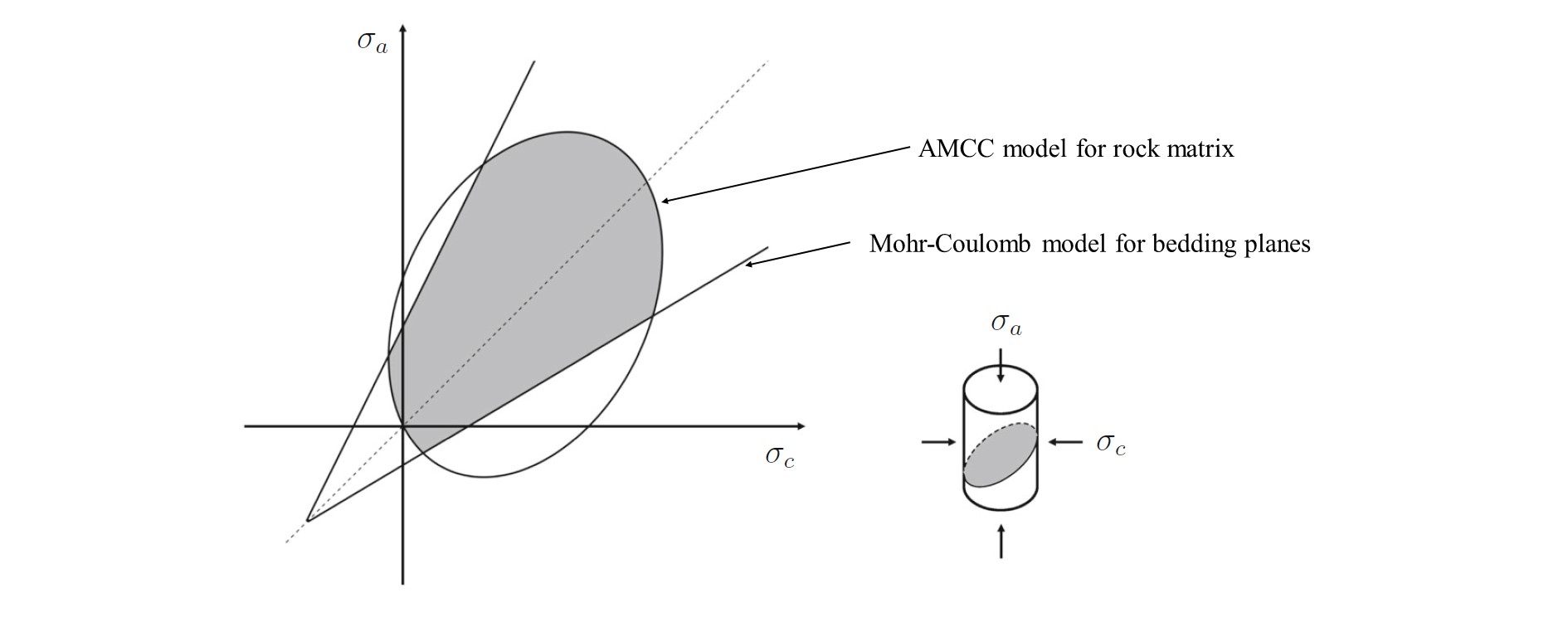

For transversely isotropic rocks, the bedding structure can result in an anisotropic rock matrix whose mechanical response can be characterized with the anisotropic modified Cam-Clay model. Moreover, the bedding planes are also weak planes along which plastic sliding can occur. These two competing mechanisms together determine the overall response of the material. Based on this concept, in addition to using the AMCC model to quantify the anisotropic response of the rock matrix, we treated plastic sliding along weak bedding planes with distinction and proposed a double-yield-surface plasticity model for transversely isotropi crocks[3].

Illustration of the double-yield-surface plasticity model for transversely isotropic rocks.

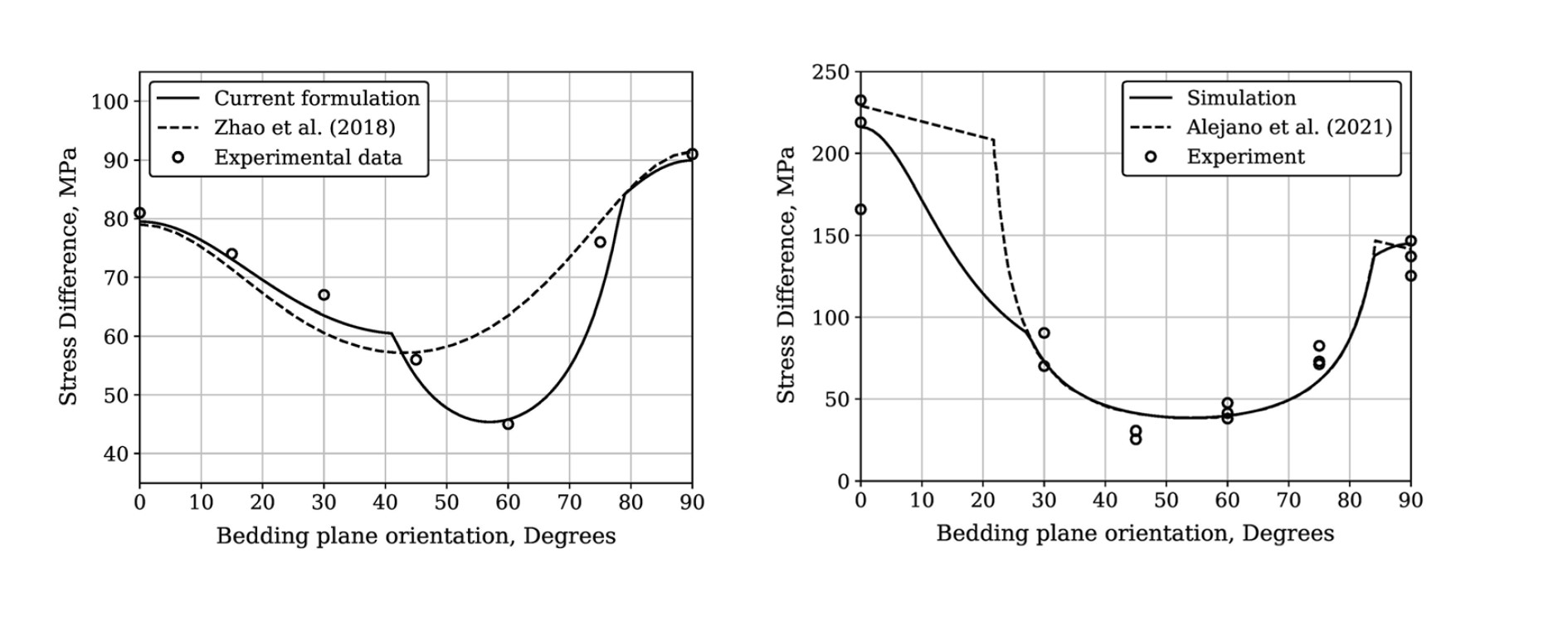

The following figure demonstrates calibrated variation curve of rock strength with bedding plane orientation. It shows that prediction generated with the double-yield-surface plasticity model will be better than that generated with the AMCC model alone, indicating that it's necessary to treat failure along the weak bedding planes as a specific and discrete failure mode.

Variation of rock strength with bedding plane orientation.

(left) Synthetic transversely isotropic rocks (right) NW-Spain Slate.

Reference:

[1] Zhao Y., Semnani S.J., Yin Q., Borja R.I.* (2018). On the strength of transversely isotropic rocks. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics, 42(16), 1917-1934.

[2] Borja R.I.*, Yin Q., Zhao Y. (2020). Cam-Clay plasticity. Part IX: On the anisotropy, heterogeneity, and viscoplasticity of shale. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 360, 112695.

[3] Zhao Y., Borja R.I.* (2022). A double-yield-surface plasticity theory for transversely isotropic rocks. Acta Geotechnica, 17(11), 5201-5221.